blog

|

February 27, 2023

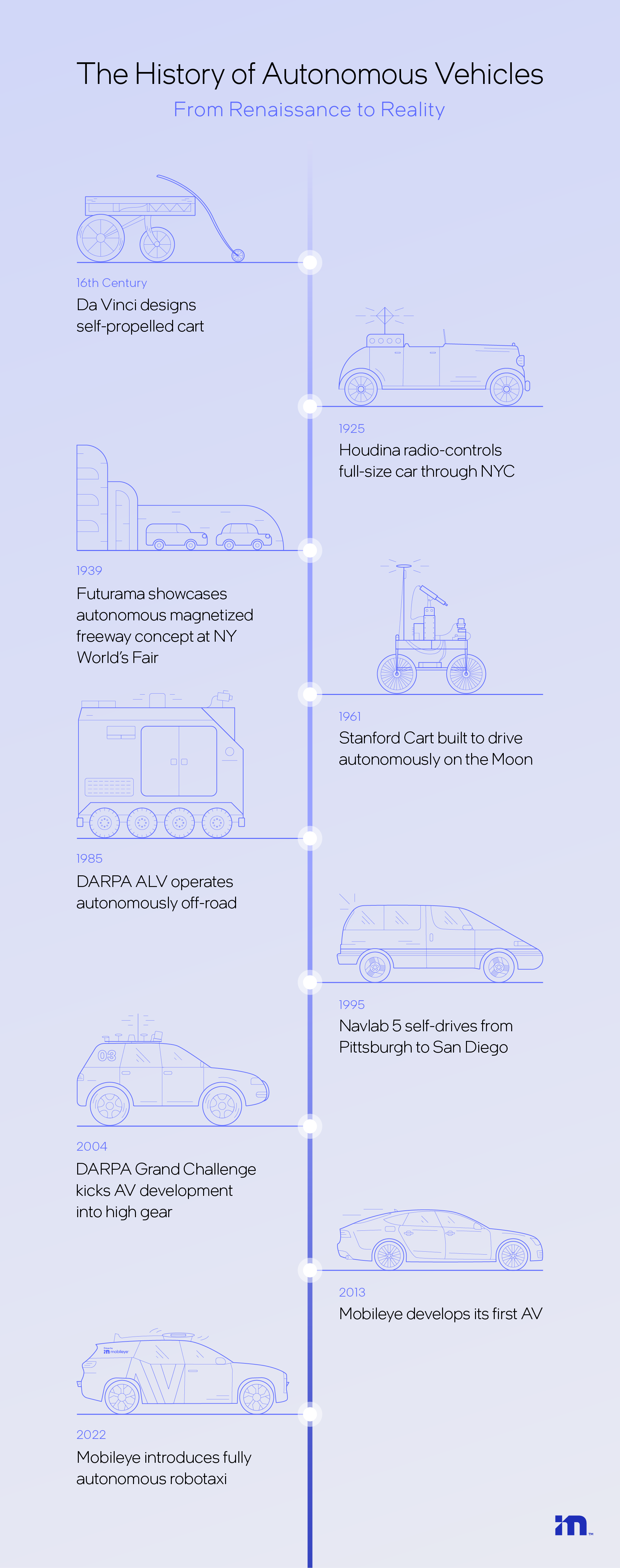

A Brief History of Autonomous Vehicles – from Renaissance to Reality

Mankind has been dreaming of self-driving vehicles for decades – even centuries. Mobileye is proud to be driving those dreams across the finish line.

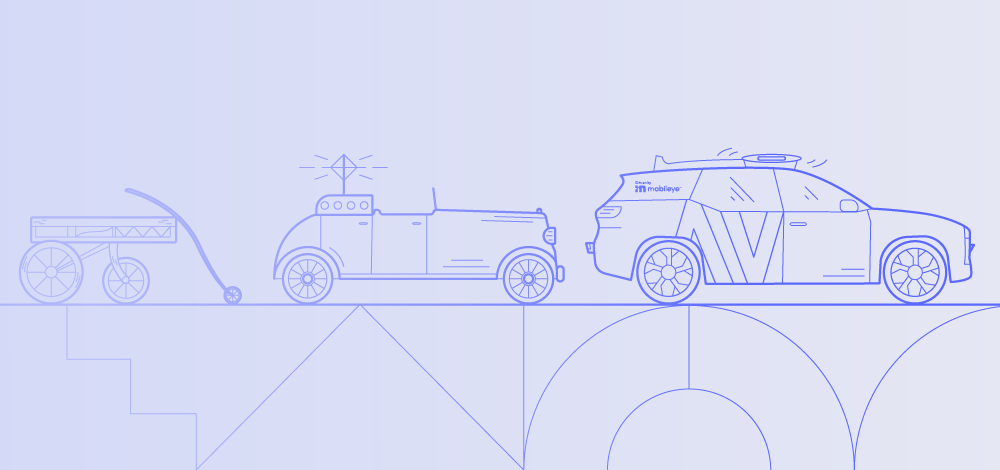

Automobiles, and autonomous vehicles especially, have evolved significantly from da Vinci's initial design to today's robotaxis.

Someday, when historians look back at this point in history, how will they characterize it? If we at Mobileye have anything to say on the matter, they’ll reflect on this as the turning point just before the dawn of self-driving vehicles. A time before anyone could order a ride in a robotaxi or purchase a fully autonomous vehicle of their own. A time when automobiles were still driven by humans, parked by humans, goods delivered by humans, and commutes endured by humans for long hours spent behind the wheel... but a time when great strides were being made to translate the long-held dream of autonomous mobility into reality.

That places us today at the precipice of a new era in automotive history. But just how long, exactly, have people been dreaming of autonomous vehicles? And what are the events that have brought us to where we are today, at this potential turning point in the evolution of human mobility?

Keep reading for a brief history of the evolution of autonomous vehicles, and the part that Mobileye has come to play in ushering in their arrival.

An Early Dreamer

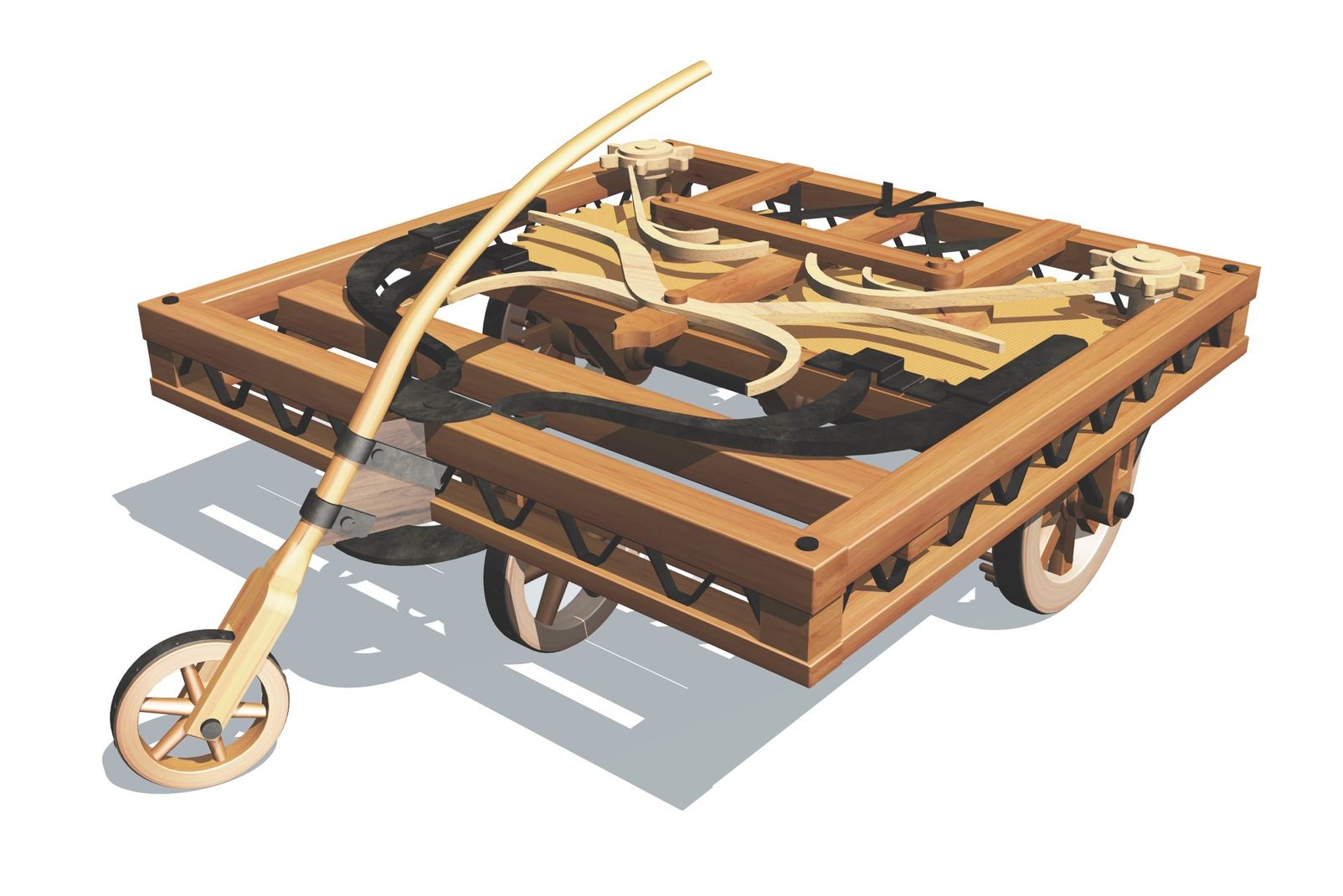

The concept of an autonomous vehicle (AV) dates back to long before the advent of the automobile itself – to the 16th century, if you can believe it. That’s when Leonardo da Vinci designed a small, three-wheeled, self-propelled cart regarded as not only the first self-driving vehicle, but the first robot of any kind. More clockwork than motor vehicle, it incorporated a series of springs for propulsion, a pre-programmable steering system, and a parking brake released remotely by rope.

In 2016, historians in Florence built a prototype from da Vinci’s original sketches. Da Vinci himself surely would not have been surprised to see it actually work as it did. But we can only imagine what he would have thought if he’d seen our AV recently driving itself through Milan, where he spent part of his life and career.

The Magnetism of the Future

It would take centuries for technology to catch up to where da Vinci left off. But when it did, the dream of autonomous vehicles rode along with it.

In 1925, electrical engineer Francis P. Houdina radio-controlled a full-size automobile through the streets of New York. The car crashed and the project failed. But as automobiles proliferated in the decades that followed, so too did efforts to automate their operation.

At the 1939 New York World’s Fair, industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes showcased a dazzling array of visionary transportation concepts. His “Futurama” exhibit featured rooftop helipads and interstate highways – as well as semi-autonomous vehicles to travel along them, using a combination of radio control and magnets embedded in the pavement.

General Motors sponsored the exhibit and continued developing the idea over the following couple of decades with its Firebird series of concept cars. Others experimented with magnetic guidance as well, but upgrading infrastructure proved too costly and restrictive to present a viable and scalable solution for autonomous mobility.

An Academic Pursuit

Academia led the next stage in AV development. In 1961, researchers at Stanford University developed a small cart to navigate on the surface of the moon using a basic form of computer vision. In 1977, mechanical engineers at the University of Tsukuba in Japan took the idea further with a passenger vehicle capable of driving autonomously at up to 20 miles per hour. Further progress was made in the mid-90s at the University of Parma in Italy – also not far from where da Vinci lived (and dreamed) centuries prior.

One of the most significant efforts came under the aegis of the Eureka PROMETHEUS Project, which brought together a consortium of universities, automakers, and tech companies in the late 1980s and early ‘90s. Funded by (mostly European) governments to the tune of €749 million (roughly €1.3 billion in today’s money), the project culminated in 1994 with thousand-kilometer (~620-mile) drive on Parisian highways that included operating hands-free, in convoy, automatically changing lanes while tracking and passing other vehicles.

Perhaps the greatest strides, however, were made once the Pentagon brought its enormous resources to bear.

The Best Defense

Through its Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the U.S. Department of Defense began supporting autonomous-vehicle research in the 1980s. Its first major undertaking in the self-driving sphere saw it fund the Autonomous Land Vehicle (ALV) project, which employed an early form of lidar to navigate off-road.

Photo courtesy of DARPA

DARPA also supported Carnegie Mellon University’s Navigation Laboratory (or “Navlab”), which produced a series of experimental AVs. In 1986, Navlab 1 – a full-size van packed with computers, sensors, and cooling systems – drove itself (slowly) around suburban neighborhoods. In 1995, the Navlab 5 minivan drove from Pittsburgh all the way to San Diego under the banner of "No Hands Across America." The onboard researchers handled the throtle and brakes while the vehicle steered itself for over 98% of the 2,850-mile (~4,600-kilometer) journey.

The floodgates really opened, however, with the DARPA Grand Challenge – a series of competitions that saw Stanford and Carnegie Mellon (among others) sparring for AV leadership. None of the contestants finished the first desert competition in 2004, but five did the following year – led by Stanford’s Volkswagen Touareg (using Intel processors). Two years later, Carnegie Mellon won the urban competition with a specially equipped Humvee.

DARPA’s competitions proved that self-driving technology could work. And that milestone in turn spurred a slew of startups, tech firms, and automakers to start their own AV development programs over the course of the following decade-plus – some of them employing former Grand Challenge contestants.

Building Blocks

While others were grappling with solving the AV question as a whole, Mobileye was already establishing itself as a leader in what would become the building blocks of self-driving technology.

Archival footage: Mobileye’s first developmental AV began testing in 2013.

From our founding in 1999, Mobileye focused on developing and supplying computer-vision technology for advanced driver-assistance systems, and our experience and track record grew steadily from there. By 2013, our technology was already incorporated into more than a million vehicles, and the driver-assist features we were enabling kept getting more advanced. But as far as we’d come, we were convinced we could go even further.

A self-driving system, we concluded, wasn’t really one system at all. It was a collection of individual functions working in unison – driver-assist functions like those our technology was already supporting. So we fitted an array of those systems to an Audi A7 and connected them to create our first self-driving car. It worked so well that our customers, who had already come to rely on us for increasingly sophisticated driver-assist technologies, begun asking us to furnish them with the hands-free driving features that our prototype demonstrated.

From Vision to Reality

As demand grew, so too did our AV development program. Our test fleet expanded and evolved from the original internal-combustion Audis to Ford Fusion hybrid sedans and NIO ES8 electric crossovers – each with an ever-increasing range of autonomous capabilities. And we dispatched those vehicles for testing in a variety of challenging locations around the world.

Along the way, we upgraded from a single forward-facing camera to surround vision. We added radar and lidar sensors, specialized AV maps, and the driving policy to share the road safely and effectively with other drivers. And we've applied the results of our ongoing AV development program to a broad range of solutions – from enhanced and premium driver-assist to complete self-driving systems.

As far as we’ve come, however, we know there’s still so much more to come. The dream of truly autonomous vehicles, held for so long by so many, is on the verge of becoming reality. And we’re proud of the role we’re playing in driving it across the line – and in teaching it to drive itself even further.

Share article

Press Contacts

Contact our PR team